In the vocabulary of a runner, patience is a dirty word. Runners always want to run faster, run more miles, and crush their personal bests and they want it now. To be more accurate, they wanted it yesterday.

I know I felt this way before I donned my coaching cap. I wasn’t satisfied with a workout unless I needed to be carried off the track and was forced to spend the rest of the day passed out on the couch. That was dedication. Surely, this is what it took to be the best runner I could be.

Unfortunately, this mindset couldn’t be more wrong.

Not only did this way of thinking impact my short-term goals, thanks to all-to-frequent injuries and bouts of overtraining, but as you’ll learn in this article, it likely affected my long-term progress as well.

As I’ve matured as a runner and changed my perspective on training as a coach, I’ve come to fully appreciate and value the art of patience. This shift in mindset wasn’t easy and it didn’t happen overnight. Hopefully, with the help of some hard, scientific data and a sprinkling of anecdotal evidence, this article can accelerate your maturation as a runner and help you achieve your goals.

Finish a workout feeling like you could have done more

This is a phrase you’ll hear from any running coach worth his or her salt. As elite coach Jay Johnson espouses to his athletes, “you should be able to say after every one of your workouts that you could have done one more repeat, one more segment or one more mile.”

Coach Jay doesn’t just pay this rule lip service. He’s known for cutting workouts short when an athlete looks like they’re over that edge. It’s one of the reasons his athletes continue to perform and improve consistently, year after year.

Now, thanks to recent research published in the European Journal of Applied Physiology, we have the scientific data to prove what good coaches have known for so many years. Patience pays off. (side note – thank you to Alex Hutchinson for first alerting me to this study through his blog)

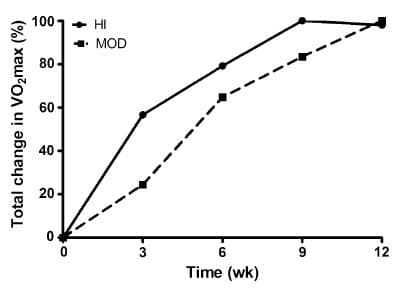

In this study, one group of athletes performed a series of workouts at near maximum intensity for twelve weeks. The researchers then had another group perform the same type of workouts (same repeat distance and same amount of rest) yet at a much more moderate intensity.

The results. The high intensity group improved rapidly, recording an increase in VO2 max 30 percent higher than the moderate group after three weeks.

Well, that doesn’t seem to support our theory that patience pays off, does it?

Luckily, the researchers went a step further and recorded changes to VO2 max for six, nine and twelve weeks under the same training methodology. This is where the results get truly interesting.

After nine weeks, the high intensity group’s improvements in VO2 max were only 10 percent greater than the moderate group. More importantly, after 9 weeks, the high intensity group stopped improving and after 12 weeks showed the same level of improvement to VO2 max as the moderate group.

After nine weeks, the high intensity group’s improvements in VO2 max were only 10 percent greater than the moderate group. More importantly, after 9 weeks, the high intensity group stopped improving and after 12 weeks showed the same level of improvement to VO2 max as the moderate group.

Clearly, this research shows that while you’ll see rapid improvements from running workouts as hard as you can in the first few weeks, this improvement curve will level off and running at moderate intensity levels will produce equal, if not better, long-term results.

Of course, like all studies, this research has it’s flaws. Mainly, both groups performed the same workouts for twelve weeks, which means the same stimulus was being applied with each session. However, I’d also point out that when training for 5k or marathon for 12 weeks, the workouts won’t vary much. Sure, the workouts will look different, 12 x 400 meters at 3k pace versus 6 x 800 meters at 5k pace, but you’re still training the same energy system.

Regardless, the data supports what good coaches have known for years.

Consistent, moderate workouts will trump a few weeks of hard, gut-busting workouts every time.

But I want to improve faster

Of course, looking at that data, most runners would still choose the high intensity approach. If the end result after 12 weeks is the same, why not make the fitness gains faster the first three to six week?

Not covered in this particular research study was the impact of injuries and overtraining on potential improvement curve and long-term progress.

It’s not surprising, and it’s been supported by numerous research studies and anecdotal examples, that increased intensity is correlated with higher injury risk. Meaning, the harder (faster) you train, the more likely it is you’ll get injured.

The problem I encounter with many runners who try to workout too hard is the injury cycle, which inhibits long-term progress because for every two steps forward, you take one step back.

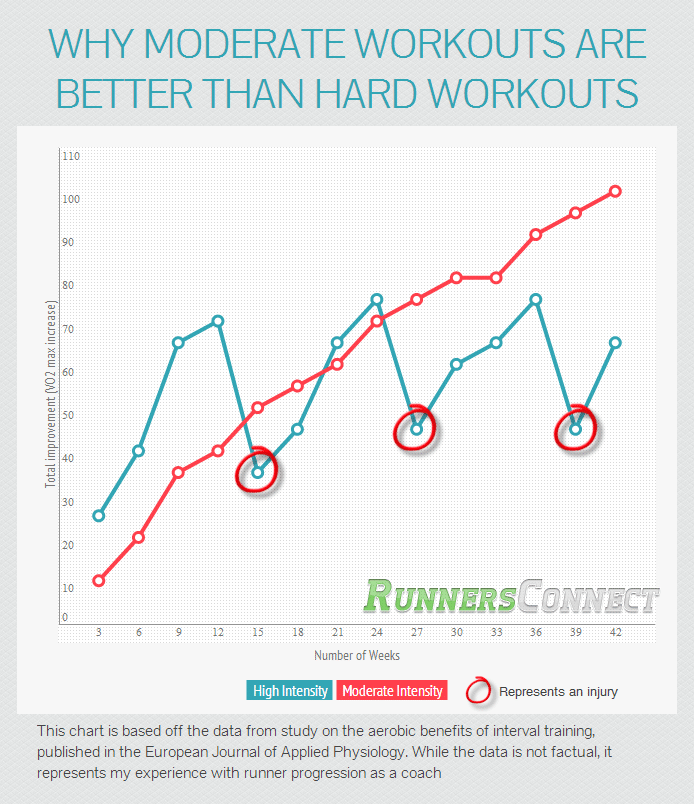

Using a similar graph to the one provided in the research study, let’s examine the long-term consequences of always pushing your workouts as hard as you can versus running moderate and always feeling like you could have done more.

While the actual improvement data in the image is fictional, it is based off the data from the actual study representing improvement curve. The difference is that I’ve extended the training period to ten months and factored in injuries and potential overtraining. This graph accurately represents my experience with trying to run every workout as hard as I could and the vast data I’ve collected working as a coach for the past eight years.

As you can see, the high intensity runner speeds out of the gait and is far ahead of the moderate intensity runner after a few weeks. However, it doesn’t take long before the high intensity runner suffers his or her first injury and is setback a week or two. No worries, with just a few weeks of high intensity training, they are back ahead of the slow plodding moderate intensity runner. However, this cycle continues to repeat itself until the high intensity runners is far behind the consentient, steady performer.

More importantly, after 42 weeks, the high intensity runner is at a point that they can no longer make up the difference in fitness simply by training hard for a few weeks.

They will continue to struggle to reach their potential until they finally learn to run their workouts at a moderate level and train to their current level of fitness.

Don’t be the high intensity runner. Learn from the mistakes of countless runners before you, the research and scientific data, and the wisdom of coaches who know their stuff.

A version of this article originally appeared on Competitor.com

10 Responses

Jeff, this is great article and it came in perfect timing. As you know, I have been formally training for 3 months now and I noticed big improvement on endurance and all other aspects but pace. I understand now that I not only have to train on endurance, pace, etc. but also PATIENCE. Thanks for this article and for your guidance thru my process.

Interesting article – I wonder how much we can extrapolate to more traditional runners workouts though? The study looked at 6-10 x 1 minute intervals on a bike – does the same apply to 800m reps of running or 1 mile reps of running? We certainly cant deduce that from the study?

What about the effect of building in recovery weeks? manipulating variables – ie I wouldnt keep athletes doing the same program 12 weeks in a row?

Here is a thought. Why not consider high intensity workouts for a short period (say 4-6 weeks) followed by moderate intensity. That way you get the added short term gains but reduce both the chances of injury and long term issues. There is no reason you have to be just one or the other.

Good point. As pointed out in this article, these studies aren’t perfect and training shouldn’t always remain the same. You need to challenge yourself with new stimulus all the time. However, your idea could still likely easily result in injury for that 4-6 weeks. Trust me, I’ve seen it happen countless times (trying to bounce back from an injury or get ready quickly after downtime). It almost always ends badly. Again, i understand what it is like to be a runner, but I have also learned (from experience) that patience will ALWAYS pay off.

for the longest time I was the high intensity runner. I read Rich Roll’s Finding Ultra and saw what HRM training did for him and I was sold. While I’m still not where I want to be as a runner, I feel like I’m moving in that direct a lot more efficiently these days.

Slow and steady not only wins the race – it makes you a better runner too!

Great article! Like other runners I have some problems to train slower and have patience. Now I’m engaged a 16 weeks marathon training and it’s hard to keep the marathon pace (I’m use to running 10k and 21k)

But this article opened my eyes about this subject!

Great article as this not only applies to runners, but all sports in general! Maxing out on lifts and workouts day in and day out will limit the long term potential of the athlete. Not only that, training in such a way opens the runner to more injury, as mentioned in the article. Being able to train healthy, is the best way to continue to progress!

Nice story !! and we shoul implement it

Thanks !

Good article. I am a heart transplant runner. Recently able to do about 3-3.5 mi (I am trying to build my miles each week) a few days a week along with some strength training days and interval training. I want to get faster, but my max hr is not the same as a normal individual and is blunted due to denervation of the heart. I can’t get my hr as high when interval training. What is the best type of training for me in order to improve my overall speed? I am having a VO2 Max test done next week, but I am curious as to what you suggest for me. Thanks for any input and help.

Hi Natasha,

Just running more miles will help a lot. Slow miles build your aerobic system and will help make you a lot faster, even more than speed work, until you’re comfortable running something like 35-40 miles per week. Hope that helps! https://runnersconnect.net/aerobic-training-run-faster-by-running-easy/